WIC's effective services are demonstrated to improve pregnancy, birth, and early childhood outcomes, but only 51.1 percent of eligible participants are certified for WIC.188 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, WIC participation has declined since reaching an historic high of 9.2 million in 2010 at the height of the Great Recession.189 With the majority of State WIC Agencies reporting participation increases during COVID-19, WIC providers are poised to reach a new generation

of participants if they are empowered with the flexibilities and technology necessary to deliver quality services in the twenty-first century.

CERTIFICATIONS AND CLINIC PROCESSES

Even though WIC providers have implemented remote appointments during COVID-19, WIC traditionally provides in-person services at community-based clinics. Participants are required to physically come to the clinic at least once every six months for health screening and assessments, but participants are often more frequently present at their WIC clinic for nutrition counseling and other touchpoints. Over a dozen State WIC Agencies require more frequent in- person contact for program participation, as electronic-benefit transfer (EBT), or e-WIC, cards must be manually reloaded at the clinic every three months.190 Appointments alternate between certification appointments and nutrition education sessions. WIC staff augment in-person visits with additional contact, through phone, texting, e-mail, and online platforms. These technologies are utilized during the COVID-19 pandemic to substitute for in-person services during the public health emergency.

PHYSICAL PRESENCE REQUIREMENTS

In 1998, Congress instituted requirements that WIC participants — including infant and child participants — be physically present for certification appointments.191 At the time, certification periods only lasted six months. Participants quickly identified the physical presence requirement at certifications as a burden, with structural barriers such as scheduling, transportation, and obtaining childcare or time off work interfering with continued WIC participation.192 Certification appointments have been shown to be as long as two hours.193 As a result, Congress extended certification periods from six months to one year for breastfeeding participants in 2004194 and for children in 2010.195

When implemented in 1998, the physical presence requirement was specifically introduced as a program integrity measure, coupled with other punitive anti-fraud measures for participants and vendors.196 Together, these provisions exceeded the boundaries necessary to protect the integrity of program services and sensationalized the extraordinarily low instances of participant fraud and abuse.197 Unsurprisingly, the first recorded participation declines in WIC program history occurred in the years following introduction of physical presence.198

COVID-19 waivers of statutory physical presence requirements have enabled greater innovation as State WIC Agencies leverage telehealth options to reach

WIC-eligible families.199 The certification appointment includes four core components:

» ELIGIBILITY SCREENING: WIC staff

reviews documents to verify an applicant's identity, residency, and income. These can be paper

documents or photos of documents shown on a screen (e.g., a smartphone or WIC computer connected to state Medicaid or SNAP system).

» HEALTH AND NUTRITION ASSESSMENT:

WIC nutrition professionals conduct an interview to assess health history, eating behaviors, and nutritional risks. A specific nutrition risk must be identified to be eligible for WIC services.200 Participants are measured for height/length and weight and blood tested to screen for hemoglobin levels and iron-deficiency anemia.

» NUTRITION EDUCATION: Individualized nutrition education counseling

is provided during a certification appointment, based on the health and nutrition assessments and the participant's concerns, interests, and priorities.

» REFERRALS AND BENEFIT ISSUANCE:

Participants must agree to rights and responsibilities, a lengthy and burdensome recitation of terms of program participation.201 Where appropriate, WIC staff will refer participants for healthcare or other services. WIC nutrition staff will assign a food package and tailor it to the participant's needs, and then issue an electronic benefit transfer (EBT)/e-WIC card.

Many of these steps can be accomplished through telehealth or online platforms, with over thirty State WIC Agencies already leveraging online nutrition education

platforms to deliver education outside of the certification appointment.202 WIC providers may explore strategies at the mid- certification appointment, which repeats many of these processes without the statutory physical presence requirements. Streamlining the initial and mid-certification appointments is a key priority for WIC providers, as repeated trips to the clinic can disincentivize continued participation. This is especially critical for families with multiple children participating in WIC, where the individual children's certification periods may not be aligned.

ONLINE CERTIFICATION TOOLS

The COVID-19 pandemic was a catalyst for WIC providers to invest in and build out technologies that streamline certification processes.203 As WIC participants

are already accustomed to utilizing technology in their daily lives and regular interactions with healthcare providers, technology platforms are critical in providing a modern, twenty-first century experience.204 In addition, technology can enable more focused time on core nutrition content instead of administrative processes, as well as alleviate burdens such as bringing the correct documents to clinic, overcoming transportation barriers, and resolving staffing shortages, especially in rural communities.205

Tools that streamline certifications vary in their scale and approach, from small process changes that improve clinic flow to more complex online participant

portals where documents can be uploaded securely in advance of a certification appointment.206 One of the core challenges of scaling up online certification tools is integrating the technology with existing WIC computer platforms, known as Management Information Systems (MIS).207 WIC MIS are complex computer platforms that manage participant records, including demographic and anthropometric data, nutrition education touchpoints, food prescriptions, and remaining balance on an electronic benefit transfer (EBT), or e-WIC, card.

Many State WIC Agencies transitioned to new MIS platforms to enable the switch from paper vouchers to EBT/e-WIC cards.208 Similar to online certification tools, EBT/e-WIC needed to integrate seamlessly with MIS software to enable participant- facing technologies that streamlined the WIC experience. Since online certification tools are more focused than the nationwide switch to EBT/e-WIC, State WIC Agencies lack the flexibility to overhaul their MIS systems to implement targeted clinic- oriented technology projects. Online certification tools must therefore integrate with existing MIS software, which may be older than systems used in the private sector. As states move beyond EBT/e-

WIC implementation, both software and equipment may become outdated and require replacement, a costly endeavor that would deplete State WIC Agency Nutrition Services & Administration (NSA) funds.

Congress could revisit its strategy of the early 2010s to provide regular, dedicated set-aside funding for MIS projects that drive forward WIC innovation.

ONLINE CERTIFICATION TOOLS IMPLEMENTED BY WIC AGENCIES BEFORE AND DURING COVID-19209

- Online Pre-Application Screener: An applicant for WIC can enter basic information (name, address, initial income information, etc.) and expect a call from WIC staff to start the certification process.

- Automated Chatbot: WIC applicants, participants, or the general public can ask questions and get answers to common queries about the WIC program. Although only available in limited states, there is evidence that chatbots support a more streamlined participant experience.210

- Two-way Texting: WIC staff can send personalized or automated text messages to WIC participants and receive responses back. This technology can be used to remind participants about upcoming appointments, what to bring to appointments, and remaining benefits to use before the end of a month.

- Document Uploader: An applicant or participant in WIC can securely submit documents (e.g., income proofs) to WIC staff by uploading a file or taking a photo of the document from a personal device. This mitigates the need to bring documents to the WIC clinic for certification appointments.

- Participant Portal: An applicant or participant in WIC creates an account and can begin an online application for WIC, update information, complete nutrition education, and see the balance of their WIC food benefits.

- Video Conferencing/Telehealth: WIC participants and staff can interact face-to-face through twoway video conferencing platforms. Before COVID-19, it was widely used to provide breastfeeding support and nutrition education.

INCOME LIMITS AND ADJUNCTIVE ELIGIBILITY

WIC was piloted as a supplemental food program in 1972 and scaled up nationally in 1974, trusted with limited funding to reshape nutrition outcomes.211 In 1978,

Congress adopted an upper income limit to ensure that the limited appropriated funding was targeted at low-income individuals with the highest nutritional risk.212 Even when implementing an income limit, Congress firmly instructed that "every effort should be made to ensure that the program reaches as many nutritionally and economically deprived individuals as possible."213 WIC income thresholds were tied to the limits

for free and reduced-price school meals, which are currently 185 percent above the federal poverty line214 — currently estimated at $23,606 for a single parent or $48,470 for a family of four.215

In 1989, Congress instituted adjunctive eligibility to waive the income test for applicants who receive food stamps (now, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP), who are part of a family that receives Aid to Families with Dependent Children (now, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF), who receive Medicaid, or who are part of a family where a pregnant woman or infant receives Medicaid.216 These provisions remain a critical method of streamlining certifications,217 with 80.1 percent of participants reporting participation in either SNAP, TANF, or Medicaid.218 More than three-quarters of WIC participants, 76.8 percent, are enrolled in Medicaid.219 The lower recorded rates of SNAP and TANF participation suggest challenges in accurately measuring cross-enrollment between these programs.220

Recognizing that the income test can be a significant barrier to participation,

USDA provides an additional option to waive the income test for certain benefit programs that are at or below the prescribed income limits.221 Some

State WIC Agencies have succeeded in designating Head Start, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), or the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) as adjunctively eligible programs, but the administrative burden of the process is significant and several states are unable to align income standards across programs.222 As with the initial introduction of adjunctive eligibility in 1989, Congress could make the policy decision to align these programs to streamline certification and enhance collaboration between WIC and early childhood programs.

WIC PARTICIPATION AND FUNDING TRENDS

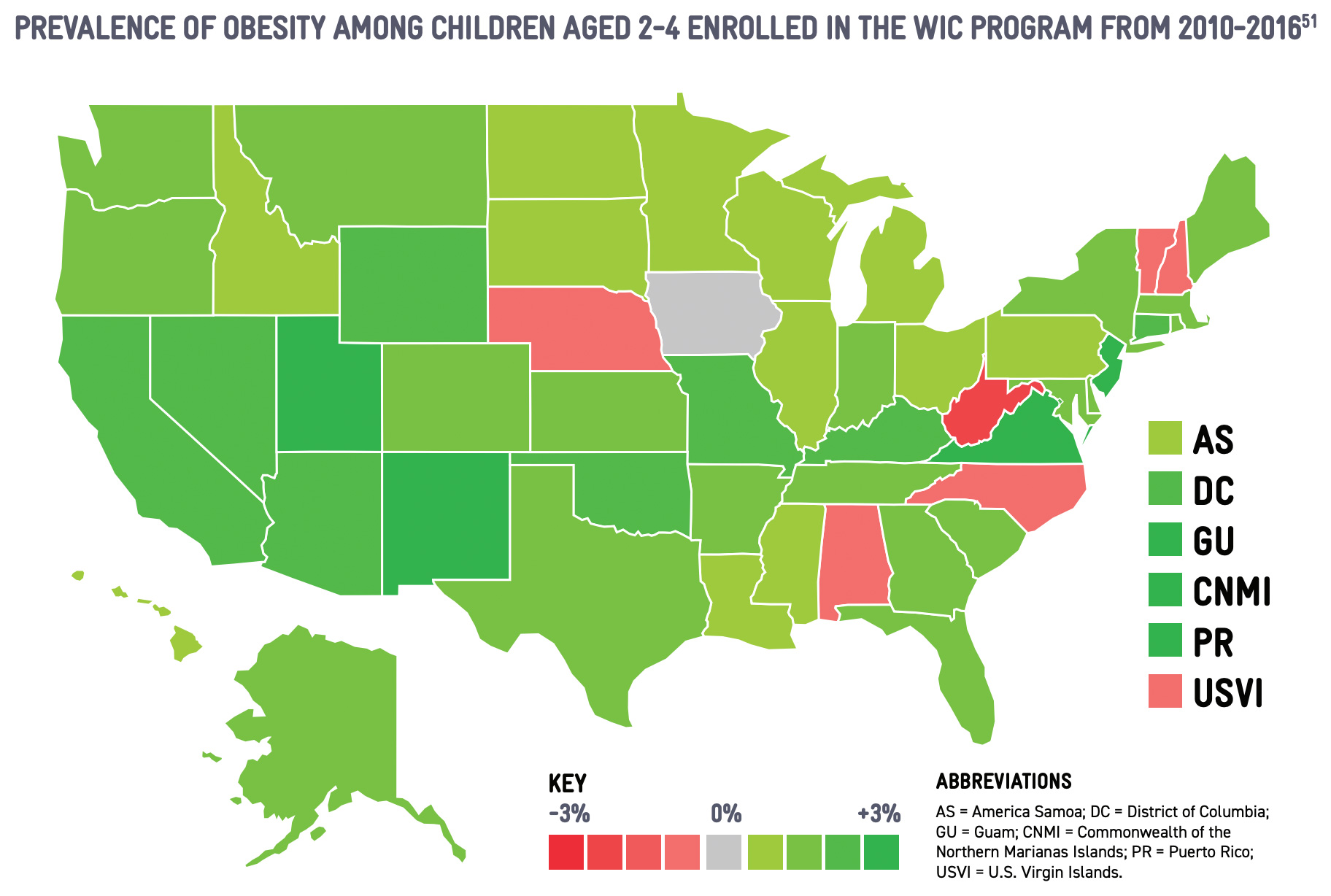

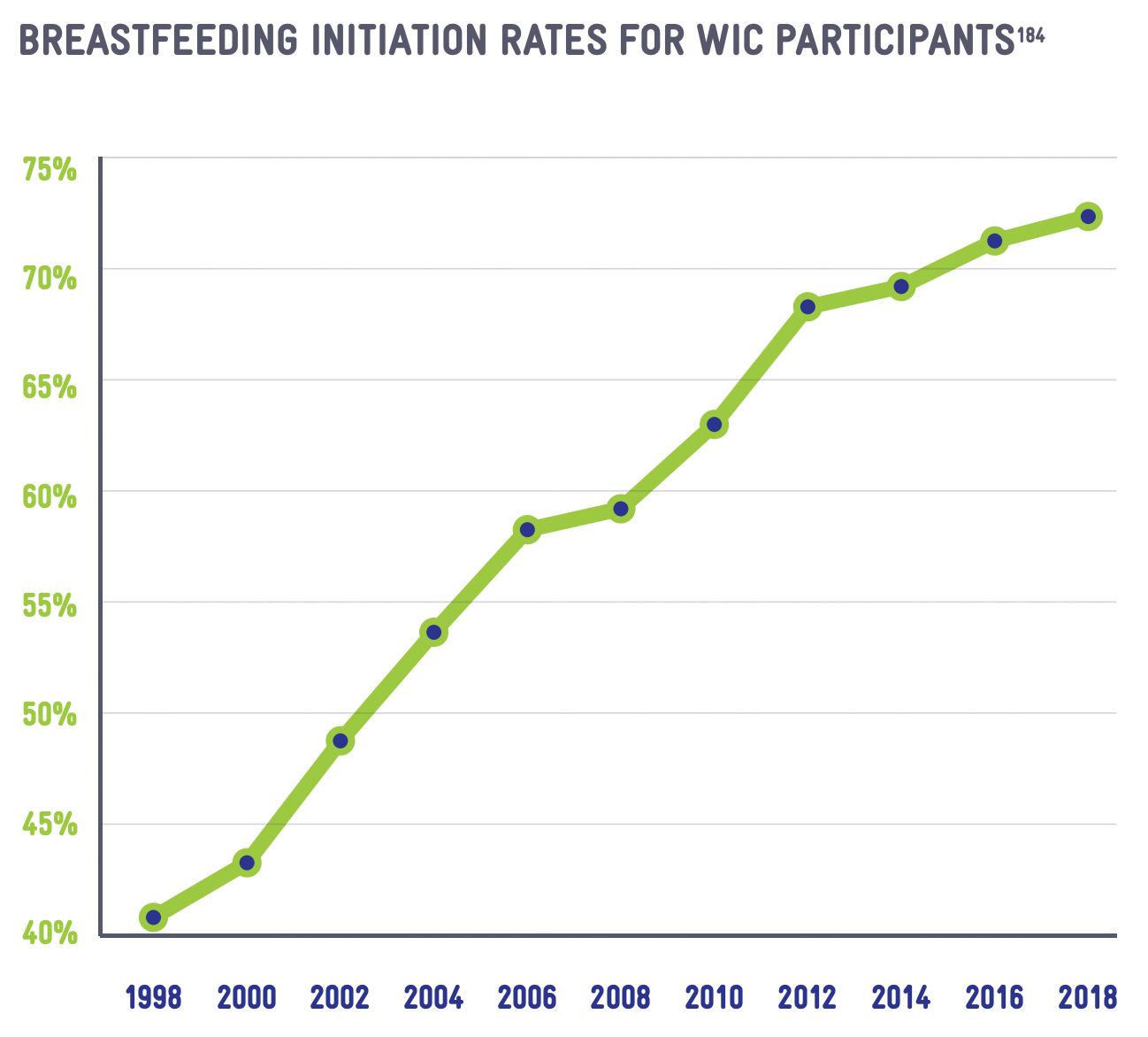

Consistent declines in participation since the program reached a record high of 9.2 million participations in 2010 pose one of the most significant challenges to WIC since its establishment in 1974.223 WIC served approximately 6.4 million participants in fiscal year 2019, marking a decline of 2.8 million participants over nearly a decade.224 This is the most pronounced decline in program history, with the only other recorded declines (totaling only 215,000 participants) occurring in 1998-2000, after implementation of physical presence and other burdensome certification requirements.225

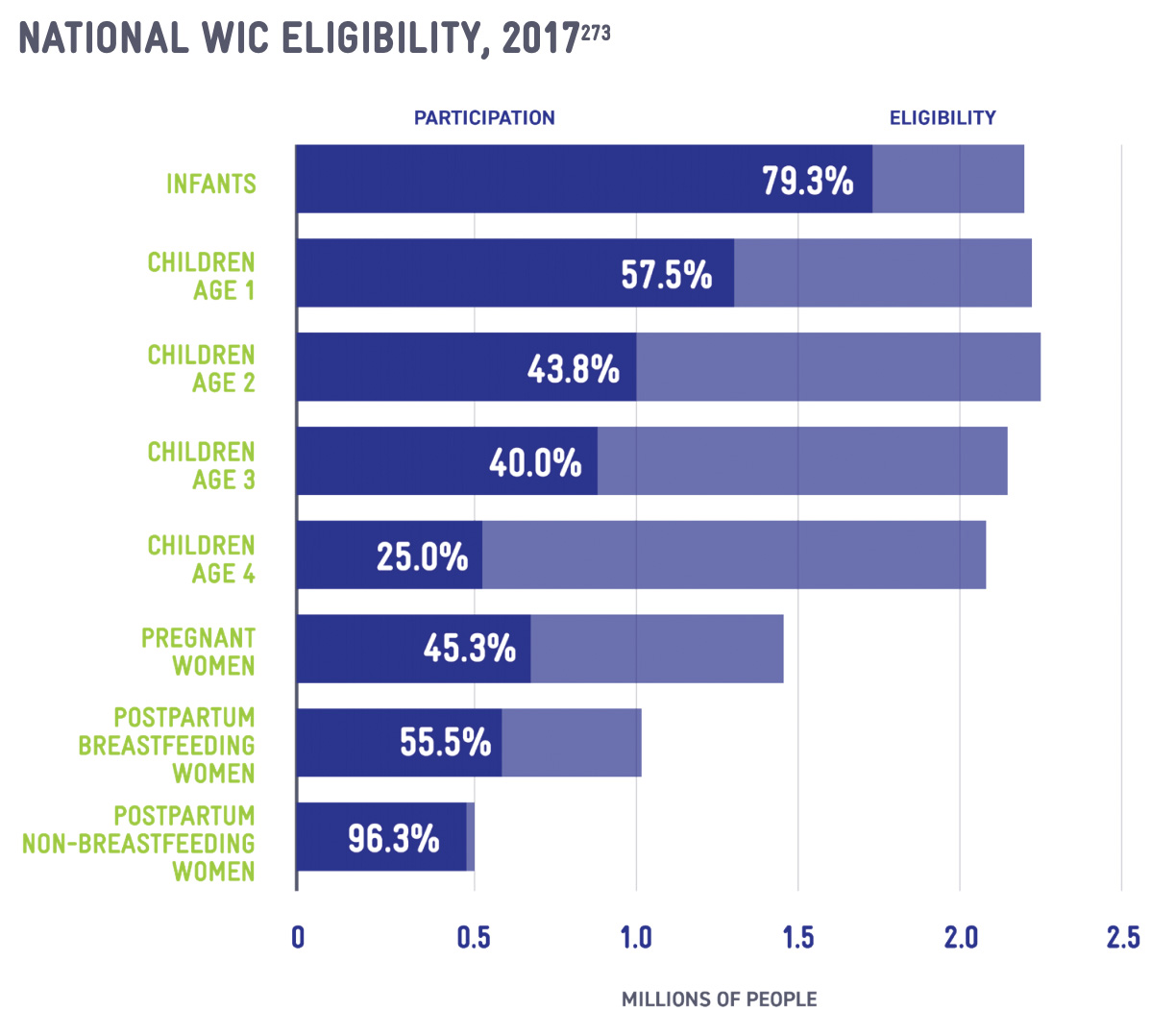

In addition to participation declines, WIC is seeing the lowest coverage rate (51.1 percent in 2017) in over a decade.226 WIC coverage rates are the percentage of estimated eligible individuals who are certified for and receiving WIC services. With the estimated eligible population relatively static, fluctuating between 13.8 million and 15 million over the past twelve years, the participation declines indicate that WIC is serving a smaller share of those who are eligible.227

In 2016, the National WIC Association (NWA) launched a National Recruitment and Retention Campaign, a multi-platform strategic marketing approach designed to raise awareness, drive enrollment, and improve public perceptions of WIC. The targeted, tested messages and branding used in the National Campaign are disseminated through digital advertisements, print advertisements in pregnancy and new-parent magazines, and point-of-care literature in OB/GYN offices, hospital maternity wards, and pediatrician offices. The National Campaign operates a web-based clinic locator, SignUpWIC.com, to connect families directly with their community WIC provider. NWA partners with 62 of the 89 State WIC Agencies to amplify the National Campaign and reach new eligible families.

BARRIERS TO WIC PARTICIPATION

Both initial access to WIC service and continued participation for the duration of eligibility are hindered by societal and structural factors. Although many barriers are consistent with challenges endured by other federal programs, WIC consistently has lower coverage rates than similar nutrition assistance programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (84 percent)228 and means-tested health programs like Medicaid (93.7 percent for children in 2016).229

One of the most significant societal factors impacting WIC participation is anti-immigrant rhetoric and federal policy change surrounding immigrant access to public benefits. Since children born in the United States are citizens at birth,230 the federal government has strong incentives to assure healthy births and positive child development. For these reasons, Congress consistently determined that WIC should continue to serve families regardless of citizenship and immigration status, even as severe restrictions were imposed on Medicaid and SNAP.231

In pursuing a deliberate strategy to reduce immigrant access to benefits, the Trump Administration ultimately came to the same conclusion and explicitly excluded WIC from review in public charge determinations.232 The final result followed years of uncertainty,

where national outlets reported that WIC could be included in public

charge.233 The associated chilling effect discouraged participation by immigrants and mixed-status families, with the Hispanic coverage rate sharply falling by 6.3 percent in 2017.234 In the face of unrelenting attacks on immigrants and the repeated threats to immigration policy, WIC has struggled to reassure immigrant and mixed-status families of the safety of WIC participation.

Social stigma also plays a significant role in accessing WIC services.235 White, non-Hispanic families participate in WIC at rates that are nearly 20 percent lower than Black and Hispanic families.236 This may reinforce societal misconceptions about WIC, with reported confusion about eligibility and ingrained concern about taking services from someone who is more in need, even though WIC is funded to serve all eligible families.237 This concern is reinforced when federal spending bills are not passed in a timely manner, as at least three State WIC Agencies limited access to WIC during the 2013 government shutdown.238 Historic use of waiting lists and priority risk systems continue to undermine messaging to eligible participants.239 Structural factors and program requirements can also deter participation, especially the yearly certification appointments. In-person requirements for certification appointments implicate a range of barriers, including scheduling difficulties, access to transportation, and obtaining childcare or time off work.240 The certification appointment at the first birthday is especially burdensome, as it aligns with transitions in infant feeding habits and the expiration of infant formula benefits. The first-year certification appointment is associated with a 21 percent reduction in the coverage rate, from 79 percent of eligible infants to 58 percent of eligible one-year-old children.241 Child coverage rates continue to decline as the children age and additional certification appointments must be held, until only one-quarter of eligible four-year-olds are served.242 Additional efforts to streamline certification and clinic ser vices, including introducing online tools and platforms, can mitigate other barriers at the clinic, including wait times at clinics.243

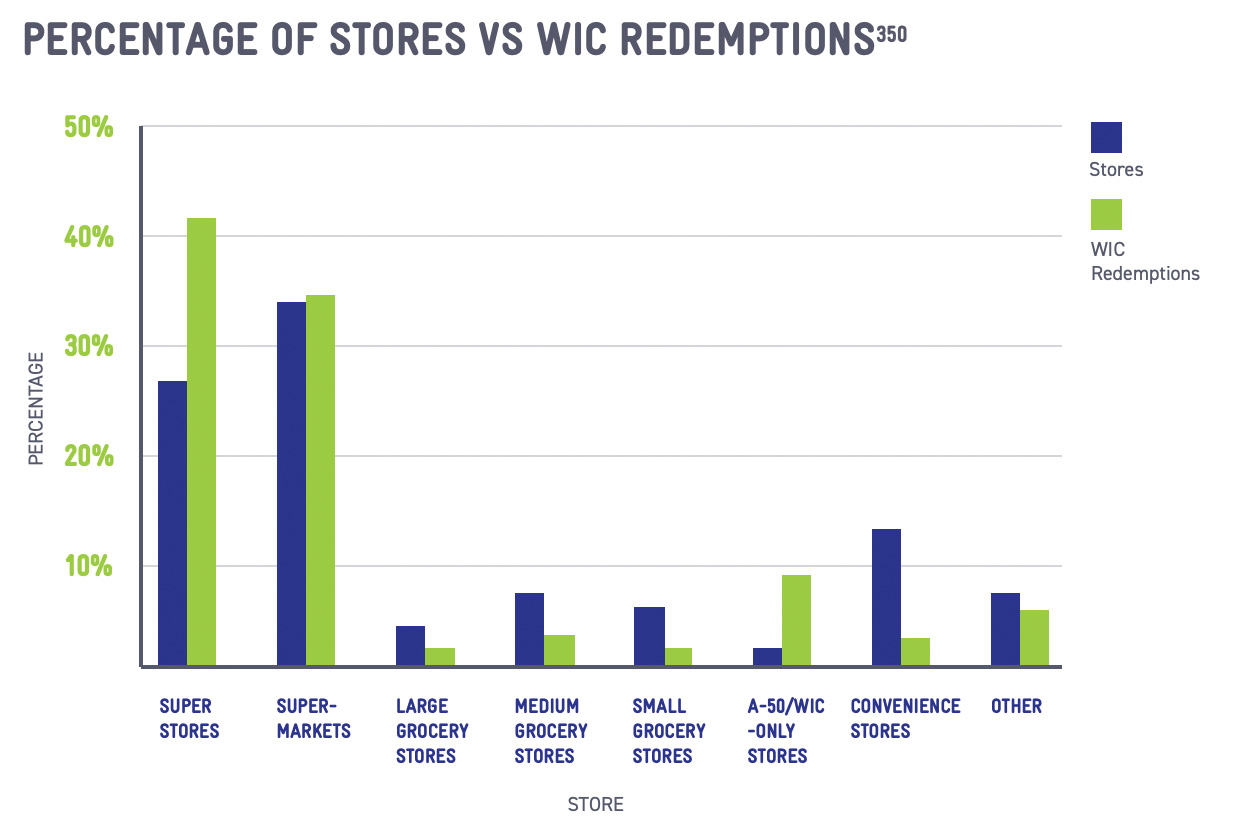

Stigma and program requirements intersect in presenting challenges in the shopping experience. Due to the prescriptive nature of the food package, participants must often navigate the store on their own to select approved items that will not complicate the

final transaction.244 Cashier attitudes, turnover, and unfamiliarity with WIC can be significant barriers to assuring a smooth shopping experience.245 Recent technology innovations, including the transition to electronic-benefit transfer (EBT), or e-WIC, cards, as well as shopping apps that can help identify approved items at the shelf, are helpful tools to mitigate difficulties for WIC shoppers.246

INCREASED PRESSURE ON WIC FUNDING

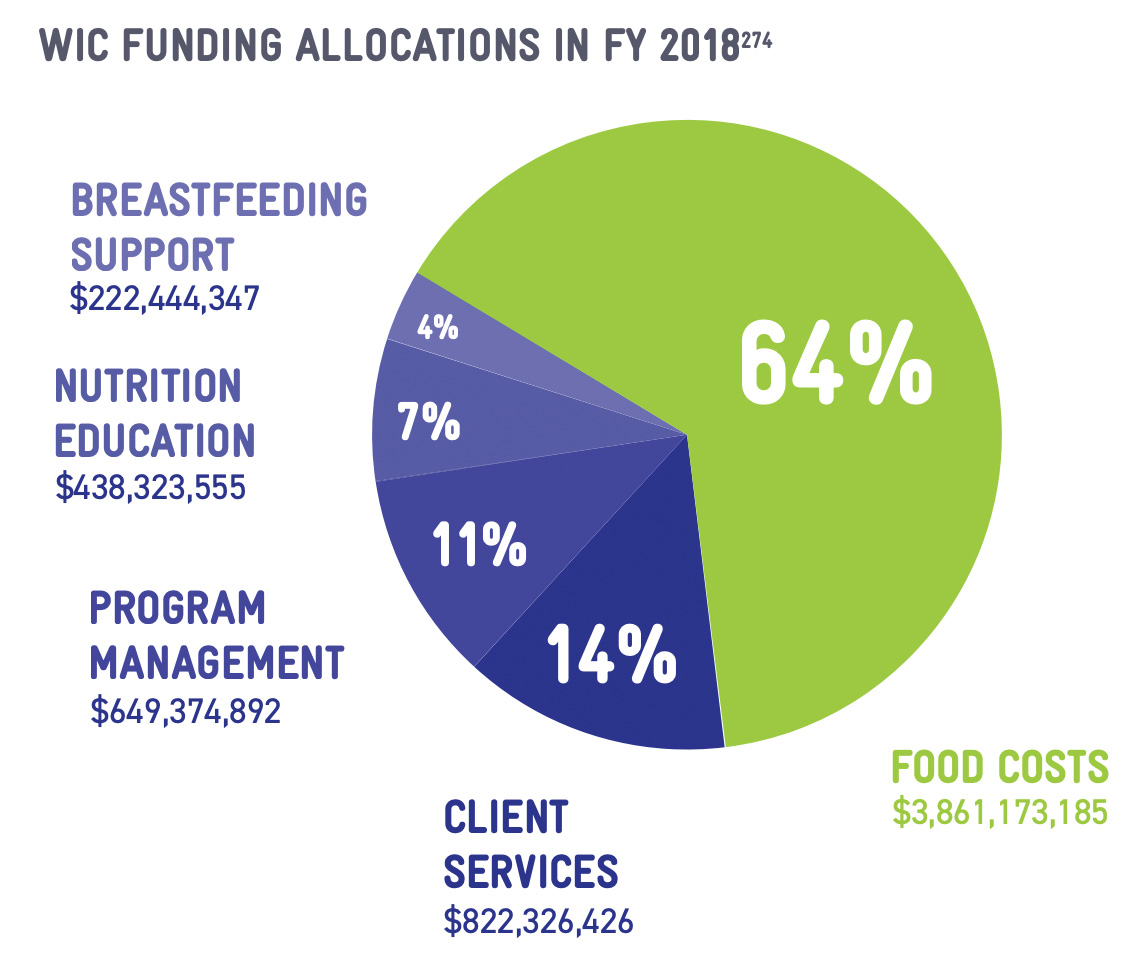

WIC is a discretionary program funded through the annual appropriations process in Congress. Participation declines throughout the 2010s spotlighted structural flaws in the funding formula that apportions federal funds to State WIC Agencies. State WIC Agencies receive two grants each year: the Food grant and the Nutrition Services & Administration (NSA) grant.247 The Food grant is limited to the issuance of benefits to participants for the purchase of supplemental foods.248 The only exception, instituted in 1998, permits Food funds to cover the purchase of breast pumps.249

The NSA grant covers all WIC costs that are not associated with direct food benefits, including a wide range of expenses such as nutrition education, breastfeeding support, technology procurement and administration, outreach and partnerships, clinic rent

and management costs, and salaries for the entire WIC workforce.250 Program administration costs are kept fairly low, constituting only 11 percent of the overall WIC budget,251 even as core management costs, such as retaining credentialed professional staff like Registered Dietitians (RDs) and International Board Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLCs), continue to rise.

Despite its essential role in providing for WIC's core mission, the NSA grant comprises only 36.2 percent of WIC spending,252 leaving limited funding to invest in strengthening WIC's nutrition education and breastfeeding programming. Only 11.2 percent of WIC spending goes to these critical services (7.4 percent for nutrition education and 3.8 percent for breastfeeding support),253 leaving WIC providers in a position of stretching every dollar to the fullest extent.

Concurrent with participation declines, State WIC Agencies assumed new costs in transitioning from paper vouchers to electronic-benefit transfer (EBT), or e-WIC, transaction systems. WIC providers estimate that the cost of running an EBT/e-WIC system, including transaction fees and targeted subsidies to retailers for transaction devices, can run at about twice the costs associated with a paper voucher model.254 Although Congress appropriated funding to support the transition to EBT/e-WIC systems, no new flexibilities in the funding formula accounted for the long-term costs of maintaining the new systems. While EBT/e-WIC is undoubtedly a step forward for the program in modernizing the shopping transaction and providing convenience for participants, the additional costs have fallen on the NSA budget and exhausted limited resources even further.

PARTNERSHIPS WITH HEALTHCARE

As the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act realigned the healthcare system toward prevention, WIC's targeted intervention at the earliest stagespositions the program as a critical support for positive lifelong health outcomes. Increased collaboration between WIC and physicians reinforces messages about preventive health, guiding families toward healthier choices that will avert or manage chronic conditions and reduce overall healthcare expenditures. With the renewed emphasis on prevention, WIC's professional workforce can be better integrated into the healthcare system and utilized in innovative ways to more efficiently provide preventive care.

STRENGTHENING REFERRALS

One of the core services provided by WIC is to conduct health screenings and make referrals to healthcare and other social services. WIC clinics routinely screen

for food insecurity, healthcare coverage, immunizations, access to dental care, tobacco cessation, opioid and substance use, postpartum depression, and other health issues, resulting in appropriate referrals to Medicaid, SNAP, Head Start, pediatricians, dentists, mental health providers, and other programs and services. WIC is a vital point-of-contact for many services, as WIC staff's consistent contact with WIC families provides a critical opportunity to raise awareness about available programs and services.

WIC makes referrals in a variety of ways, including by providing information directly to participants, asking participants to directly follow-up with the service, hiring patient navigators or family support coordinators to assist WIC families in connecting with services, or integrating data systems with other programs to generate automated referrals.

With WIC participation declining, similarly strong referral policies from other programs could have a pronounced effect on breaking through societal misconceptions about the availability of WIC services and reinforce the continued value of WIC services as children grow older. Trusted medical professionals — including physicians, OB/GYNs, pediatricians, and nurses — can have a significant impact on influencing patient decisions to follow up on a referral to specific services.255

In 2015, the National WIC Association utilized funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to strengthen referral networks at WIC clinics in Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, Texas, and Virginia. WIC providers created green prescription pads to screen for food insecurity, breastfeeding support, or medical risk. The pads were distributed to community partners, including healthcare providers, Head Start, grocery stores, and military bases. The low-cost, effective tool was utilized to refer families to their local WIC provider.256

Community partnerships will look different for each WIC provider, and strong referral networks depend on consistent collaboration between WIC and healthcare providers. In some states, the State WIC Agency will establish or facilitate an advisory council to provide a regular forum for coordination and partnership with the medical community, including maternal health, pediatric health providers, and HMO providers.257 This can lead to innovative partnership, such as Medicaid covering the costs of transportation for WIC participants to get to the WIC clinic.258

State governments can also partner on a broad range of projects that promote cross-enrollment between programs like WIC, SNAP, and Medicaid. State-driven projects to develop universal applications or screening tools are effective at reducing paperwork burdens for applicants, although states must account for the challenge of WIC's in-person requirements.259 Even more limited partnerships, such as New Hampshire's efforts to design a WIC dashboard within the SNAP online application tool,260 can connect families with WIC services or provide WIC with relevant information to conduct follow-up outreach to eligible families.

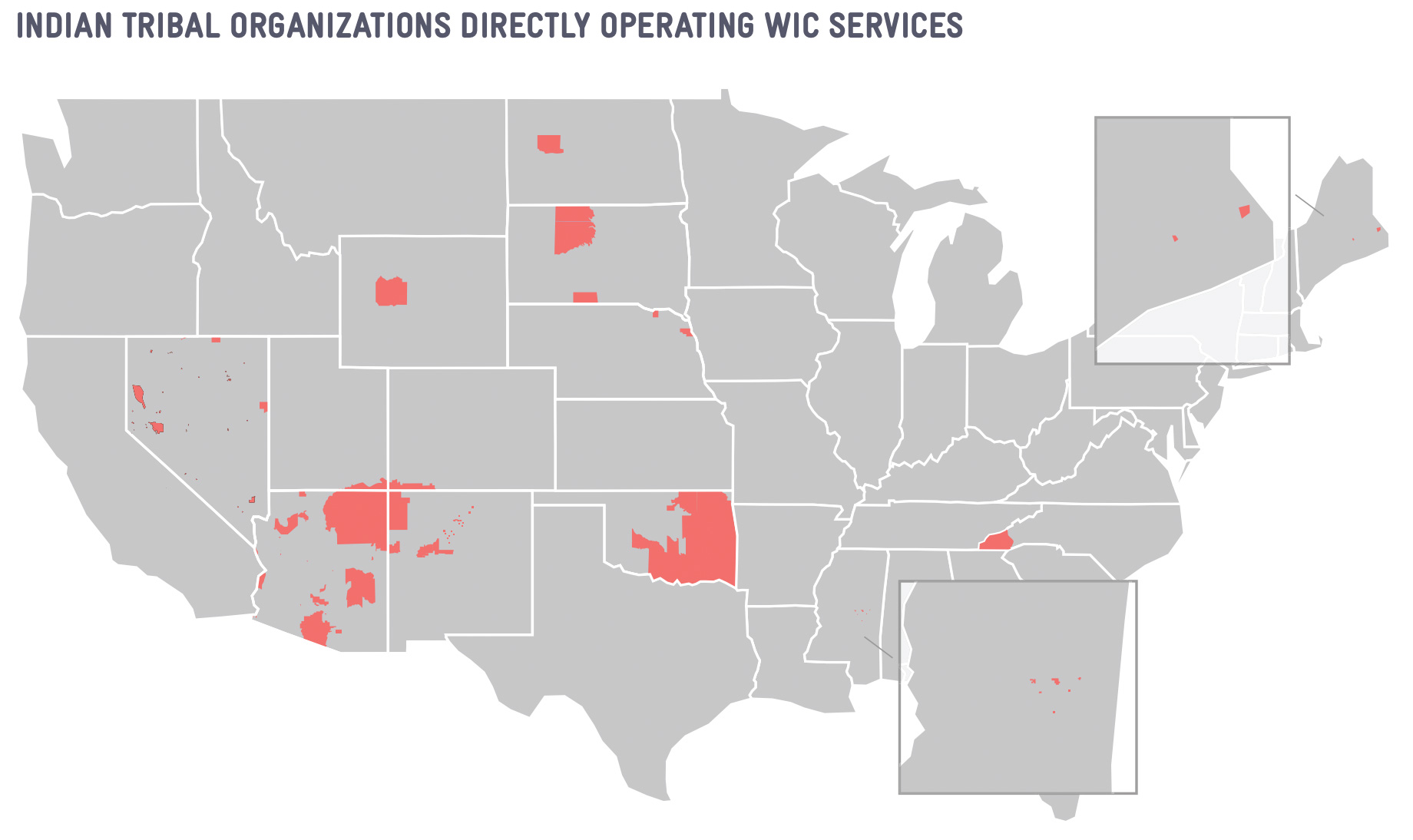

Some State WIC Agencies have explored more ambitious data-sharing projects to identify eligible families through Medicaid or SNAP administrative data.261 More than three-quarters of WIC participants, 76.8 percent, are enrolled in Medicaid,262 suggesting that eligible individuals who are not certified may also be accessing Medicaid. Federal data indicates that only 33.3 percent of WIC participants access SNAP,263 which suggest challenges in accurately measuring cross-enrollment between WIC and SNAP and offers opportunities for greater collaboration with SNAP administrators.264 To address inequities in serving Indigenous communities, future collaborations should also be inclusive of the Indian Health Service (IHS) and other tribal services.

One of the key challenges to enhanced data sharing is the need for robust memorandums of understanding (MOUs) between relevant agencies that govern data management. In several states, SNAP, Medicaid, and WIC are positioned in three different state departments.

Complex agreements that may implicate data privacy laws like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) take time to negotiate before any data sharing can commence.265 Many states — including small, rural states — lack resources to manage complex data- sharing projects or capacity to analyze the data in a meaningful manner.

GO-TO WIC: COMMUNITY-CLINICAL LINKAGES

WIC clinics are operated by nearly 1,800 local agencies and can be located in a variety of venues, including hospitals, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), county health departments, and standalone clinics.266 No matter the venue, WIC providers have routinely partnered with medical and public health stakeholders in the community to raise awareness about WIC and address community health concerns, including providing services to low-income and vulnerable populations.267

As a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's emphasis on prevention, WIC providers, especially those co-located at hospitals or FQHCs, have strengthened community-clinical linkages to partner more effectively with the healthcare system and public health agencies. Community-clinical linkages are more formal partnerships that support community access to resources that help prevent, manage, or reduce risks of chronic disease.268 Integrated care is essential during pregnancy, as families often receive support from a range of healthcare providers and community groups, especially if there are underlying chronic conditions such as type-2 diabetes.

WIC providers in Washington State and California have implemented effective models to leverage the WIC workforce in providing preventive services. At a FQHC in Washington State, WIC splits the time for Registered Dietitians with other clinical nutrition and chronic disease management services that bill Medicaid, including diabetes prevention programs and medical nutrition therapy.269 An agency in California formed a coalition with hospitals and physician groups to coordinate breastfeeding support across Los Angeles, ensuring consistent, quality support through numerous entry points.270

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, health plans were required to cover chronic disease management and preventive services.271 The WIC workforce is rich in nutrition and breastfeeding expertise and in some states, is the largest employer

of breastfeeding and nutrition support staff.272 As the healthcare system adjusts toward prevention, the WIC workforce is well positioned to provide additional services that can be billed to Medicaid or private insurance plans to improve overall health outcomes.